(note that blog posts are published in parallel through our Local Disturbances podcast)

Recently, we have become curious about how AI-generated text might serve to disguise satire. In the past, satire has often camouflaged itself in other genres (fairy tales being a favourite) to avoid retribution from powerful institutions (e.g., the church), the aristocracy, or powerful individuals. So, the style was fixed, and the content was layered onto the familiar style. Satire can be dangerous work. Historically, satire has served to ridicule prevailing dogmas and behaviours. When those dogmas and behaviours are backed by the power of violence, precautions become necessary.

Perhaps surprisingly, the word satire doesn’t come the Greek satyr, mythical creatures with their exaggerated erections. It comes from Latin, from satura such as in lanx satura, a full dish. Satire, therefore, is a filling up, an overflowing, a medley of ingredients. Sure, it might make you laugh, but it’s the aftertaste that lingers.

What makes satire interesting is its double-voiced nature. It bites with a kind of tenderness. Satire occupies the husks of other genres and in doing so creates a tension between the container and the contained. Rage steps inside the body of a children’s story or a popular song or a cartoon and both sides are changed as a result. And the shells then become a disguise, refracting the rebellion within.

How can you be so angry about a cartoon? A children’s story? A funny song?

Generative language arrives a corpse. Other people’s words are dug up, combined together, and something ‘new’ – but empty - emerges. How might we occupy these empty shells of language? How might we turn them over to the work of subverting the assumptions of the dominant culture or authority through humour and chaos?

Over the past months, we've been trying to map out this process of occupation and corruption, to invite tension, and to re-purpose synthetic speech to other ends. Rebellion, in and of itself, is the end. We are not worried about the contents of the hegemonic stories that threaten to embrace us, but the strength of their grip.

Part of this exploration will form a chapter in the forthcoming Poetics of Synthetic Language book from UKAI Projects

What follows are some thoughts on using synthetic language as a mask for satire.

This work comes out of the Poetics of Synthetic Language residency we ran in 2023. What does the ‘thingness’ of generative language allow us to say or do that we currently cannot? How might subversive ideas be cloaked in a data object? How might artificiality serve as a mask or filter and where might this be useful (and hilarious)?

Those accused of subversive speech, like in Reynard the Fox stories in the Renaissance, would say “why are you so upset, it’s a fairy tale!” and in the same way we are curious if satire can be delivered today with the admonition of “why are you so upset, it’s AI-generated”.

What qualities do AI-generated utterances possess? Fairy tales are for children. Cartoons are innocent fun. AI-generated speech is just probability and prediction and represents our culture’s collective instincts. What qualities do we reflexively assign to synthetic language? How might this be exploited to make culture?

Satire and Bakhtin

Bakhtin also had a significant interest in the role of satire in literature and culture. For Bakhtin, satire was an important genre because of its ability to subvert, challenge, and invert the official norms and ideologies of the time. His analysis of satire is most famously applied to the work of the French Renaissance writer François Rabelais in his book "Rabelais and His World".

Bakhtin’s concept of satire is deeply connected to his theories of carnival and the carnivalesque. The carnival was a time when traditional rules and hierarchies could be reversed, and the norms of society were openly mocked. This temporary suspension of the established order allowed people to interact in a free and uninhibited way.

Satire, in Bakhtin’s view, inherited the spirit of the medieval carnival. It was a literary mechanism that allowed authors to use humour, wit, and the grotesque to undermine the seriousness of official language, truth, and authority. Through exaggeration, parody, and ridicule, satire could expose the artificiality and hypocrisy of societal norms, making it a powerful tool for criticism and change.

For Bakhtin, therefore, satire wasn’t just a literary genre but a mode of subversion against official and authoritative discourse. It was a way of speaking "from below," giving voice to alternative perspectives and challenging the power structures of the day with the laughter and irreverence characteristic of carnival.

Mechanically, satire often works by inhabiting forms of speech and inflecting them in ways that points both to their original meaning and to a ‘doubled meaning’ superimposed on the first. Satirists often occupy forms and genres that are deemed innocuous. This is often done (at least initially) in contexts where the satirist faces significant risks to their safety. This is a testament to both the power of satire (and laughter) as a form of political commentary and social critique and the courage of its creators. Throughout history, satirists have often braved the dangers of censorship, imprisonment, and even death to voice dissent and highlight injustice.

By occupying seemingly innocent forms such as fairy tales, government documents (samizdat), cartoons, or news websites (The Onion) the satirist amplifies the impact of the ‘doubled speech’ while also distancing themselves from risks associated with unpopular ideas.

“How can a cartoon hurt you?”

Medieval Satire (Europe)

The medieval period saw satire in the form of fabliaux, short comic tales in verse, and in Chaucer’s "The Canterbury Tales," which used irony and humour to critique social norms. Satirical messages were also conveyed through troubadour songs and minstrel performances.

Renaissance and Enlightenment Satire (Europe)

The invention of the printing press in the 15th century allowed for the wider dissemination of satirical literature. Jonathan Swift’s "Gulliver’s Travels" and Alexander Pope’s satirical poems are examples of the satirical literature of this period. Visual satire became prominent with the advent of printed illustrations and caricatures.

19th and 20th Century Satire (broad)

Satire in the 19th and 20th centuries often appeared in newspapers and magazines, like Punch in the UK and The New Yorker in the US. Political cartoons became a popular form of satire, as did satirical novels such as George Orwell’s "Animal Farm."

Today, even with the anonymity of the internet, satirists in various countries face doxxing, threats, and legal action. In some countries, online satirical content can result in charges of defamation, cybercrime, or even terrorism.

The materiality of satire has evolved alongside technological advances, from oral traditions to print and digital media, each medium adding its unique qualities to the satirical message. Satire remains a powerful tool for social commentary and critique, with its forms and materiality reflecting the technological and cultural contexts of its times.

Once example that we love is the samizdat, the forerunner to zines and other self-published works that often exist on the social and cultural periphery and thereby offer a point of view not always accessible to us.

In the Soviet Union, samizdat, or self-publishing, was a form of dissident activity where individuals reproduced censored and underground publications by hand, often using typewriters, and passed these documents from reader to reader. Typewriters and printing devices required official registration, which made them tools of grassroots resistance to evade official censorship. The Erika typewriter, for instance, was commonly used for carbon copies in Russian samizdat production.

Before the early 1960s, offices and stores submitted samples of their typewriter fonts to the KGB so that any text could be traced back to its source, a method used to prosecute illegal material production. Privately owned typewriters became a practical means for reproducing samizdat due to restrictions on photocopying machines, with copies typically made on carbon or tissue paper, which were easy to conceal and distribute within trusted networks.

The physical form of samizdat was distinctive—hand-typed, often blurry, wrinkled pages with typographical errors and nondescript covers—which became a symbol of resourcefulness and the rebellious spirit of the Soviet people. They looked ordinary and unworthy of attention. They were disguised as the everyday ephemera of a large, bureaucratic state. The form itself, over time, became as significant as the ideas it conveyed, elevating the act of reading samizdat to a clandestine and valued activity.

Generative Language as a Vehicle for Satire

We have recently become interested in how the form and genre of synthetic language might serve as a vehicle for satire. When one is told that a particular text was created by an AI, several interesting things happen.

Perceptions of Agency

Individuals who prompt AI are afforded less agency in how the product is understood. The human, as a prompter, is provided some distance from the AI’s outputs. While this doesn’t assign the AI any ‘agency’ in a literal sense, We do find that people are less accountable for the meaning and social value assigned to the generated utterances if their intention wasn’t to generate offensive content in the first place.

For example, our research director served as a guest director for Transitional Forms, a Toronto-based synthetic media company. The tool he was testing out was driven by a language model that is used to provide content for three virtual ‘actors’, in Unity, who act out a scene based on my initial prompts, the choices we make, and the new prompts we insert in real time. In service to our GROUND project, We were curious about how we might train a language model to simulate a circular phenomenology of time. In the West, we implicitly assume a linear model of time, a straight line from past to present to future. This has not always historically been the case, and we wanted to know if a large language model could simulate this.

What happened was interesting, and frequently offensive, as the ‘actor’ assigned the role of embodying a circular model of time would offer up “Indigenous” quotes and stories, real or hallucinated, from various communities and nations, distributed across a broad swathe of the continent. We were disturbed by these outputs but felt only partially accountable for the statements as they were very far from my intentions and were clearly a result of qualities of the model. The recording of the event has since been deleted.

Utterances are Given Collective Weight

We are becoming well-versed in the failures of large language models. They embody our collective biases and reproduce patterns of oppression and discrimination. They hallucinate, fabricating evidence without grounding in the world. We start to see synthetic media through the lens of these experiences and this gives a peculiar gravity to AI-generated language. “It must have come from somewhere”, we rationalize, even if that ‘somewhere’ is an unpleasant part or corner of our social and cultural lives. Even hallucinations follow their own strange logic. The model fills in gaps with what is ‘most likely’ but untethered to situated cognition or embodied experience. Even when understood as a fever dream, utterances extend from the mind of dreamers. How might these associations be reversed in service to satire and comedy?

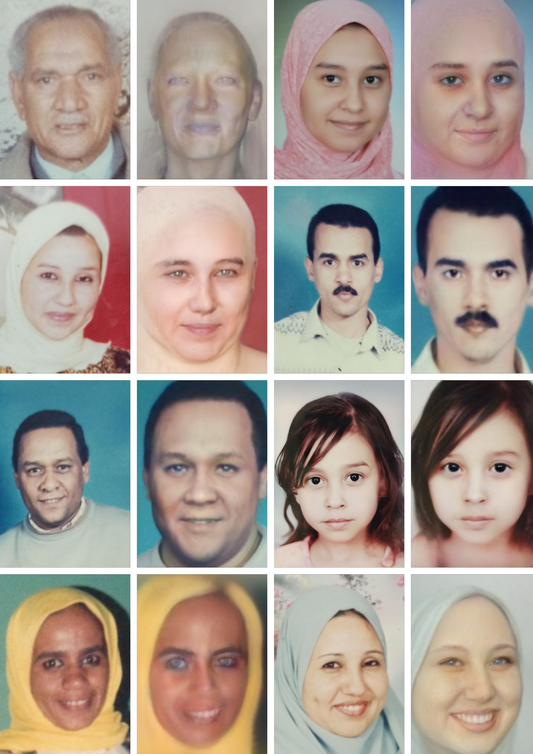

We can look to the attention received by “Loab” for some hints of how this might play out. Loab was the “AI-generated demon” summoned in September of 2022. Loab was brought into existence by Supercomposite, an artist, looking to make the opposite of “Marlon Brando”. Supercomposite was using negative prompts and the negative of Marlon Brando was apparently a weird logo. Another negative prompt applied to the weird logo didn’t bring us back to Marlon Brando, but to Loab.

The idea that a demon was lurking in these language models was a compelling one. Within a day of Loab’s arrival she was being described as a queer icon, was being unironically understood as a demon, was being analyzed as evidence of multiple different types of bias, and a lot lot more (including a proposed movie project).

The reality of why Loab kept appearing was far more banal but a general need to identify a source and meaning for Loab speaks to how synthetic media are understood and processed.

Utterances are Products of Prediction

Another assumption we have about objects of synthetic language is that they represent access to patterns and predictions unavailable to us as individuals. Even AI’s sharpest critics dismiss the technology as simply figuring out “what comes next”. AI generated language is understood, consciously or otherwise, as the product of mathematical prediction and optimization. It is the final step in a long, complex process full of formulas and very powerful computers. We might find the outputs bland, or contrary to our expectations, or cliché, but we take for granted that they are the product of some black-boxed process.

It's a bit like checking a weather app. We don’t need to understand how the weather is predicted, but we assume that some process has been applied to generate a number like “60% chance of rain” and that while accuracy may vary, it is not some random output untethered from my expectations or data drawn from weather in the past. Validity is contested, certainly, but that contestation is rarely ontological.

In other words, while we might argue about whether the weather app's prediction will turn out to be right or wrong, we generally accept that the prediction itself is a real and rational attempt to forecast the weather based on scientific principles, rather than something arbitrary or wholly disconnected from reality.

The same logic applies to the outputs of generative language. We give it weight because we assume that the outputs are the result of a highly technical and goal-oriented process. Whether this assumption is accurate is beyond the point. We receive the outputs as having some processual validity.

Next Steps

So, what comes next? I've been prototyping some applications for this, including an Eco-fascist robot in Iceland and an immersive game to be launched in early October 2024. The goal has been to apply this conceptual approach to satirical works aimed at a range of political, social, and cultural spaces that react strongly to critique or laughter.

So who should we be trying to laugh at? What forms might that take through generative language?

I’ll share the outputs of that next time out and would love to hear your ideas (and your favourite works of satire) in the meanwhile!

If you like this, please share.